Miami is steeped in art and culture. It’s home to the world’s largest collection of art deco architecture, as well as Cuban-American pop artist Alex Yanes, whose vibrant sculptural paintings have garnered him an international following.

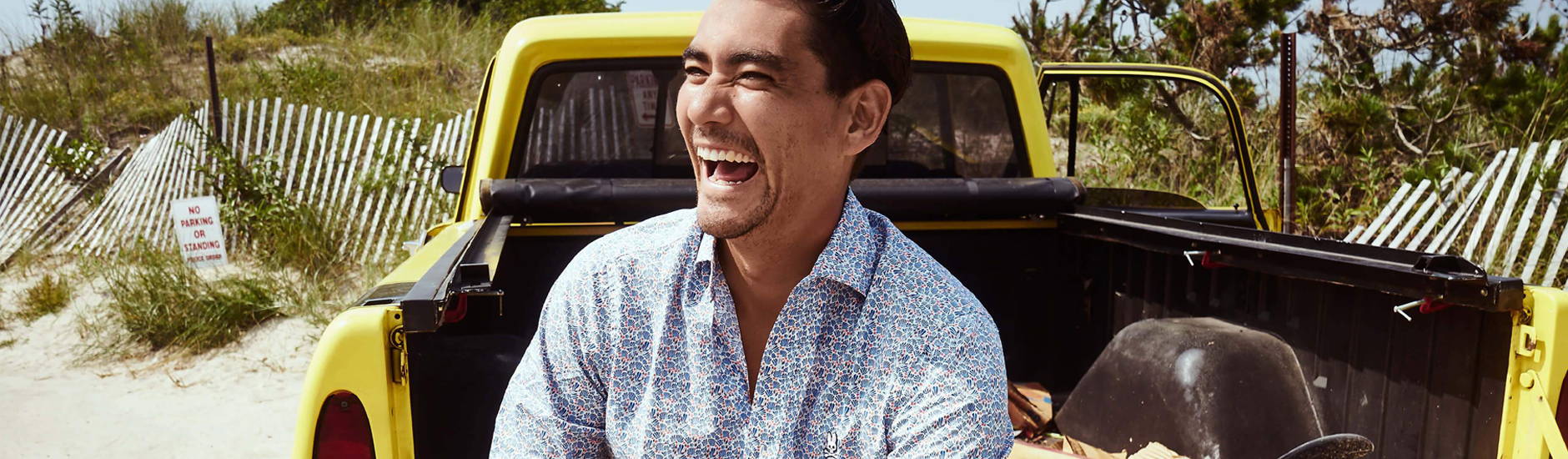

Men of Mischief: Alex Yanes

When deciding on South Florida as the location for the first North American Psycho Bunny store, it was a no-brainer to enlist Yanes to create a site-specific installation for our Aventura Mall popup as well as two limited-edition tees.

The son of Cuban immigrants whose parents immigrated to South Florida in the early 60s, Alex was born and raised in Miami and still lives there today. “It’s the only place I’ve ever lived — it's woven into me and my fabric” says the 41-year-old artist clearly very inspired by his surroundings. Three years ago, he had an opportunity to relocate westward to LA, but with his large family all living close by, his wife and him to decided to stay put and raise their three daughters in Miami as well.

“Miami is just like a melting-pot of so many different cultures: Latin, Jamaican, Haitian, there is some of all of that here — that’s what I love so much about Miami”. With no shortage of color and a wealth of international flair and flavor, we couldn’t agree with Alex more.

We visited the artist in his studio to see him in action, talk about how skateboarding led him to art, and learn more about his process.

How did you get into skateboarding?

When I was ten years old, my next-door neighbour’s older brother Chad was the coolest guy I knew. He was into skateboarding and he started building ramps; we didn’t have any skate parks in Miami then. My dad has always been really handy and DIY, and since he worked for a big hardware supplier we had a garage full of tools. This was well before the internet, so in 1988, I mailed 5$ to Thrasher magazine, and they mailed me back blueprints for a launch ramp, and I was hooked.

How did skateboarding lead you to discovering a passion for visual arts?

Going to skateboard shops and seeing the walls of decks with graphics on them, those were some of my first memories of really paying attention to artworks. Also, as a kid my cousin and I would go camping behind the lake house where our grandparents lived. There was a train track by the woods where we would build forts and go on hiking adventures, and one day when we were out there, a train rolled by with boxcars that had vibrant 1980s graffiti on them and it was the coolest thing I’d ever seen — dots were beginning to connect in my head. Fast-forward a few years and I began taking art classes in middle school and hanging out with some graffiti writers, I've always been attracted to counter-cultures.

“Going to skateboard shops and seeing the walls of decks with graphics on them, those were some of my first memories of really paying attention to artworks.”

Do you feel some parallels between the creativity of skateboarding and your art practice?

Definitely — some of what I’m doing these days being involved in larger scale commissioned works like the installation I’m doing for Psycho Bunny need to be planned in advance for other people to see on paper and approve, but all of the work I make for say a gallery show or an art fair is spontaneous and improvised much like skating. I don’t even sketch anything out before I start — I just have a basic idea and I start building stuff and see where it goes.

Improvisation is the key to a lot of the best creative work isn’t it?

The best pieces in my eyes have always been ones that were never planned. Some of my favorite work has been the result of happy accidents: a reaction with the paint and it didn’t dry right and I had to start over, or even deconstructing pieces that were almost done, and mixing them up with components from another piece to create two new pieces altogether. That’s a great thing about my work, that I can combine elements like that — they’re almost like jigsaw puzzles in that way. If there wasn’t spontaneity in it, it would feel like work [laughs].

That’s a really rare thing to have — to make a living doing something that doesn’t feel like work:

I’m 100% grateful for being able to do what I do every day — especially because of how many people told me I’d never be able to accomplish this — I don’t think of it as a job at all. In art school, my teachers were all telling me how hard it was to make a living as a visual artist, and encouraging me to study graphic design to have a solid plan B to get a job. I really had no interest in sitting behind a desk making real estate ads, so I stuck with it and worked hard, and thank god I did. There were a lot of hard times, and for a long time more downs than ups but eventually the miracle finally happened for me.

That’s a really important message for kids today — that most things worth doing are hard and take a lot of work:

I get DMs all the time from kids who are about to finish high-school and they want to know which are the best art schools they should go to, and I always tell them to just make work — it’s all about putting in work and perfecting the craft. I don’t know if that can really be taught. It’s about waking up in the morning with that idea in your head and wanting to bring it to fruition, that’s the challenge that drives me every day. I have no idea what else I would do.